Yesterday I posted a nice long post about yoga and the abdominal muscles, and it started to get a little too long & unwieldy. So here's the second Yoga Abs installment; scroll down a bit if you missed the first.

I said we'd talk about rotations in regards to the abs. Rotational

asanas like Revolved Triangle or Revolved Side Angle engage the

internal and external obliques, which are key muscles for developing a strong abdominal wall. The obliques also stabilize your spine when you rotate the trunk and pelvis. For example, when you kick a ball, the obliques rotate your pelvis. When you throw a ball, the obliques pull your shoulder around. These muscles also stabilize your vertebrae to maintain spinal alignment when you lift heavy weights. Our center of gravity lies just below the navel.

The

transversus abdominus also plays an important role in maintaining a toned abdominal wall. You engage this muscle when coughing, sneezing, or exhaling forcibly. Unlike the other three abdominal muscles, the

transversus doesn't move your spine. We use it a lot when working with the breath. To really get a sense of contracting this muscle,

try this: Rest your hands on your thighs. Take a deep inhale, then exhale completely while contracting your abdomen up & in to expel the last bit of air from your lungs. Then, without drawing in any new air, begin counting out loud: "One, two"...etc. You will feel your

transversus cinching around your waist tightly, like a drawstring. Before the lack of oxygen becomes uncomfortable, relax your belly and gently draw the breath in again. The

transversus is what we use to maintain

Uddiyana Bandha (your "Flying Up" Abdominal Energy Lock).

Breathing with the belly - If you breathe mostly by using the rib cage muscles, without using the diaphragm's power, you're limiting your breath. And if your abdominal muscles don't release, your

diaphragm can't descend fully. That's why yogis balance abdominal strength with flexibility. Remember that deep, diaphragmatic breathing does not mean pushing your belly out deliberately. Full belly breathing just requires a naturally alternating engagement and release. To make sure you are practicing deep diaphragmatic breathing, first engage the abdomen in a complete exhalation, then allow your lungs to fill up naturally, relax the abdomen, but try not to push it outward. Observe the flow from the lungs to the belly, back and forth. Lay on your back in

Savasana (Relaxation or Corpse Pose), breathe slowly and deliberately, feeling the strength of your inner core as your obliques and deep

transversus muscles compress, expelling the air from your lungs completely. Then take joy in the flow of

oxygen & prana that fills your chest as these muscles release, creating space for

prana to flow into your heart center like water flowing into an ocean. Observe without criticism. Imagine your abdominal cavity as the container of your deepest wisdom, and feel the energy at your navel radiating outward throughout your body. Breathe.

Stretching out those abdominal muscles after working them is important.

Backbends such as Supported Bridge or Up Bow are helpful, as are poses such as Up Dog and any other

asanas that lengthen the front of the body. If you feel too much tightness or any pinching in the lower back, this is due to the low back being used as a hinge, instead of distributing the arch evenly

througout the spine. So remember, the low back is not a hinge! And keep the butt muscles engaged to protect it.

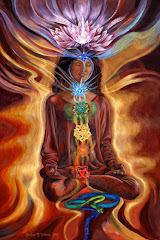

In many healing and mystical traditions, the belly is seen as an important center of energy and consciousness. Tantra yoga sometimes depicts the navel as the home of

rajas, or solar energy. In

Tantric practice, the yogi stirs up

rajas in the belly by using the breath, helping to create a "divine body" filled with

prana. This is partly why Indian gods are often shown with large bellies. In

Tai Chi, the lower abdomen is designated as a reservoir of energy. If you're not into

esoterics, consider the research of Michael

Gershon, M.D. "You have more nerve cells in the gut than you do in the combined remainder of the peripheral nervous system,"

Gershon says.

Gershon is the chair of the department of anatomy and cell biology at Columbia University's College of Physicians and Surgeons at Columbia Presbyterian Medical Center, and he says he's sure that our thoughts and emotions are influenced by our gut.

Gershon came to this fascinating conclusion through his research on serotonin, an important brain chemical many of us know of in relation to mood stability. It turns out it also plays a role in the bowel. Operating independently from the brain, a giant nervous system that

Gershon calls the "second brain" works silently in the abdomen.

Gershon explains that this belly-brain, scientifically known as the

enteric nervous system, doesn't "think" in the cognitive sense—but it continually affects our thinking. "If there isn't smoothness and bliss going up to the brain in the head from the one in the gut, the brain in the head can't function,"

Gershon says. So if we keep our tension, unhappiness, nervousness, etc. trapped in the belly, or if we don't make peace with our belly as it is, we are interfering with our own ability to feel mentally at peace.

Throughout practice, we'll continue to strengthen the abs while keeping them supple, and more importantly, really understand which muscles we're working with internally. Focusing on the belly during practice is a great gage of how things are going. Is there room for the breath? Are you able to maintain

Uddiyana Bandha?

Keep observing without judging. As you tap into this power center over time, it will vastly expand both your mental and physical practice.